Is a Roth Conversion During Graduate School the Right Move?

Going to graduate school full-time brings a significant change in your life. Amid the upheaval, there’s a powerful — often overlooked — financial strategy that could save you significant money in the long term on taxes: a Roth conversion.

When you shape your day-to-day around grad school, it’s hard to think of anything beyond the next due date, let alone your tax situation in 40-plus years. However, if you can extend your time horizon, executing a Roth conversion may result in significant tax savings for you.

What is a Roth conversion?

A Roth conversion transfers money from a traditional, pre-tax retirement account (commonly a 401(k) or Rollover IRA) to a Roth IRA. While you’ll pay income taxes on the amount converted, all future growth and qualified withdrawals will be tax-free from the Roth IRA.

If you left the funds as is in your 401(k) or Rollover IRA, you would owe taxes on the initial contribution and the growth when you withdrew the funds in the future. You did not pay taxes on this money when you (or your employer) contributed the funds into the account. The government will want to take its share of the tax-deferred growth.

Enter the Roth conversion strategy. The strategy triggers income taxes on the converted amount, but all future growth & withdrawals will be tax-free. Individuals in graduate school will likely be in a lower earning year due to a lack of full-time employment, allowing the conversion to take place at low marginal tax brackets.

Roth conversions may not be suitable for all investors. Tax implications and eligibility for financial aid or credits should be carefully evaluated. But during a year when you are attending graduate school full-time, it can be especially impactful.

Leverage a lower tax bracket

The primary reason to consider a Roth conversion during a low-income year is simple: you’ll likely be in a lower tax bracket. Graduate students often earn stipends, part-time wages, or work a summer internship. Others might take time off between jobs or go through a career transition — all of these result in significantly reduced income for a year or more.

You pay ordinary income tax on the amount you convert to a Roth IRA. If your income drops to $25,000 or less, you’re likely in the 12% federal tax bracket (or even lower, depending on deductions and credits). Converting funds from a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA during that year means you pay far less in taxes on that money than you would by converting in your peak earning years or while withdrawing in retirement.

Why timing matters with a Roth conversion

Maximize flexibility and reduce future RMDs

Roth IRAs aren’t subject to required minimum distributions (RMDs) during the owner’s lifetime. Traditional IRAs force you to start withdrawing — and paying taxes — starting at age 73-75, depending on your birth year. Roth IRAs offer more control over when and how you use your retirement money.

Reducing future RMDs avoids pushing other income into higher tax brackets in retirement by having a smaller pre-tax bucket from which you’re drawing. Converting small amounts now can create long-term tax diversification and flexibility.

Front-load tax-free growth

Once funds are in a Roth IRA, they grow tax-free—and withdrawals in retirement are also tax-free, provided you’re over age 59½ and have had the account for at least five years. That means the earlier you get funds into a Roth IRA, the more years of compounded, tax-free growth you’re locking in.

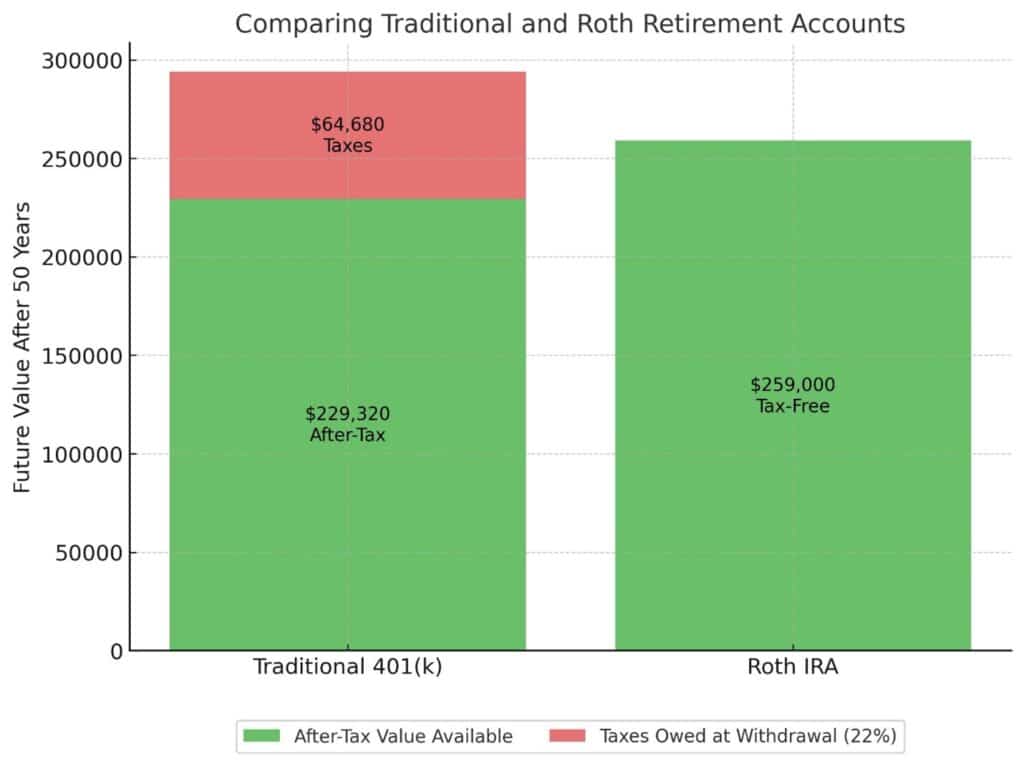

Let’s walk through a hypothetical scenario. (Keeping in mind that this is an example for illustrative purposes only. Actual outcomes depend on individual circumstances and future tax policy, and are not guaranteed.) You have $10,000 in an old 401(k) that you decide to execute a Roth conversion on during your 2nd year of graduate school. You’re in the 12% marginal tax bracket and owe $1,200 to the IRS. You planned to rely on these assets in retirement, and let’s assume you’re one bracket higher (22%) than your current 12% bracket in retirement. Let’s look at how that plays out:

On the left, we have the non-conversion scenario. Using a hypothetical 7% annual interest rate compounded annually, this $10,000 value has grown to $294,000 over the last 50 years – you will now owe taxes on any balance withdrawals. If these were all in the 22% tax bracket, you would approximately $65,000 in taxes brings your net value to around $229,000.

On the right, we have the conversion scenario. By completing the Roth conversion and paying $1,200 today, you now have $259,000 of assets that won’t be taxed at all in the future. You also will not be required to draw on these during your lifetime, and any inheritors of the assets won’t ever owe taxes on withdrawals.

In this hypothetical, the counterpoint is that if you are in the 12% tax bracket when withdrawing these assets down the road, you’ll end up in the same position. This is true, but there are also many unknowns. You likely saved other assets towards retirement, and the above only shows the growth of $10,000 of assets. With required minimum distributions starting at 75, you likely quickly bump out of the 12% bracket. We are also uncertain about the direction of future tax law, given the current federal deficit. One could see a future world with higher marginal tax brackets. Paying $1,200 today could save you around $30,000 in net value in this theoretical ($229k after tax in the non-conversion scenario vs $259k in the conversion scenario), and who knows how much more if brackets change. That’s a small price to pay to not have to worry about future tax changes.

A Personal CFO approach to tax planning

At Brighton Jones, we take a holistic approach to tax planning. That means we don’t look at this decision in isolation. Our Tax Advisory team works hand-in-hand with your Personal CFO team to evaluate:

- How a conversion could impact your eligibility for financial aid, credits, or grants

- Whether you have cash on hand to cover the tax liability

- How this move fits into your broader financial goals, including real estate, philanthropy, and long-term investing

This isn’t about making a quick tax decision — it’s about designing a plan that aligns with your life and maximizes your impact.

While Roth conversions make sense in many low-income situations, it’s wise to consider a few caveats. Make sure you have cash available to pay the taxes on the conversion. Additionally, graduate students receiving tax-free scholarships or grants should verify how taxable income from conversions may impact their financial aid or credit eligibility.

In short, taking advantage of a low-income year — such as graduate school — to convert pre-tax retirement savings into a Roth IRA is often a wise and strategic decision. With careful planning, this move can set you up for decades of tax-free growth and flexibility in retirement.

This content is for informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as individualized advice. For individualized advice tailored to your specific circumstances, please consult with your adviser.